9 What to track on Git and Github?

9.1 Approach 1 : Track statistical code only

Some people use Git and Github to track changes to their statistical code only. Here, they are only tracking their code files in R (.R or .Rmd), or SAS (.SAS), or the corresponding files for whichever language they use.

They add all other types of files to the .gitignore file so that Git won’t track them or accidentally push them to GitHub. Under this approach, untracked files include: data files, word documents, PDFs, image files, etc – anything else you are storing looking in the folder tracked by git that you do not want pushed to GitHub.

This approach most closely corresponds to how GitHub is used by software developers/other code writers, and is used by researchers and research teams depending on their objectives.

9.2 Approach 2: Track statistical code, some data files, images, and other documents

Some people use Git and Github to track a variety of files including their code, some of their data files, as well as images and other documents. This approach is often used by advocates of reproducible research, and to give outsiders a fuller picture of an entire research project.

Sometimes, you can post your data, if it is unrestricted and not too large. In this case, you can set up your GitHub so that all of your data visualizations as well as a completed report can be reproduced by someone who is not affliated with your project.

In many research or public health settings, you are not able to share the data. In this case, you can still share other aspects of your project with the wider community.

9.2.1 Data files do’s and dont’s

❌ Don’t track restricted data!

Restricted data cannot be posted on GitHub. A best practice is to store it securely outside of your tracked folder to ensure there is no chance of it being posted.

❌ Don’t track large datasets!

Git will warn you if your file exceeds 50 MB and block you from tracking files 100 MB or larger. To ensure these files aren’t tracked, you can store them elsewhere (outside of the tracked Git folder), or store them in the tracked folder while also listing them or their file type to your .gitignore file.

❌ WARNING FOR MAC USERS: UNDER NO CIRCUMSTANCES SHOULD YOU TRACK .DS_STORE files!

If you are a Mac user, you may not even know what a .DS_STORE file is. These are

invisible files that are created whenever you view a folder using Finder. You

will see them when you write git status. You do not want to track these files

as it can allow people to hack your computer!! As a best practice, add these

to your .gitignore file to ensure that they are never tracked by you or anyone

else contributing to your project.

🤔 Consider tracking intermediate data products

Generally, it also doesn’t often make sense to track a large “raw” data file – it is too big and not useful to track any changes to this file. It may be helpful to track “intermediate data products”, if these files are not restricted. Intermediate data products might include aggregated datasets that are either reported directly or used in analysis. For example, you may have access to a restricted dataset, but the data may become non-restricted if you aggregate at the level of the census tract. The benefit of tracking this smaller dataset is that if the raw data is updated, you can easily see how those updates affect these intermediate data products if you track them. In this case you need to ensure you are not reporting any private/restricted data (eg no cell counts below 10 is a restricted often imposed on aggregated tables, or not reporting any identifying features such as protected health information or anything else that would allow anyone with access to identify individuals.

✅ Do track plain text data files (e.g., csv and txt files)

These are best for tracking because they render nicely on GitHub, so you can easily view the differences to these files when you submit a pull request. You could also track things like Excel files but you can’t easily view them on GitHub, so some of the benefits of using GitHub do not apply to these files.

9.2.2 Images dos and dont’s

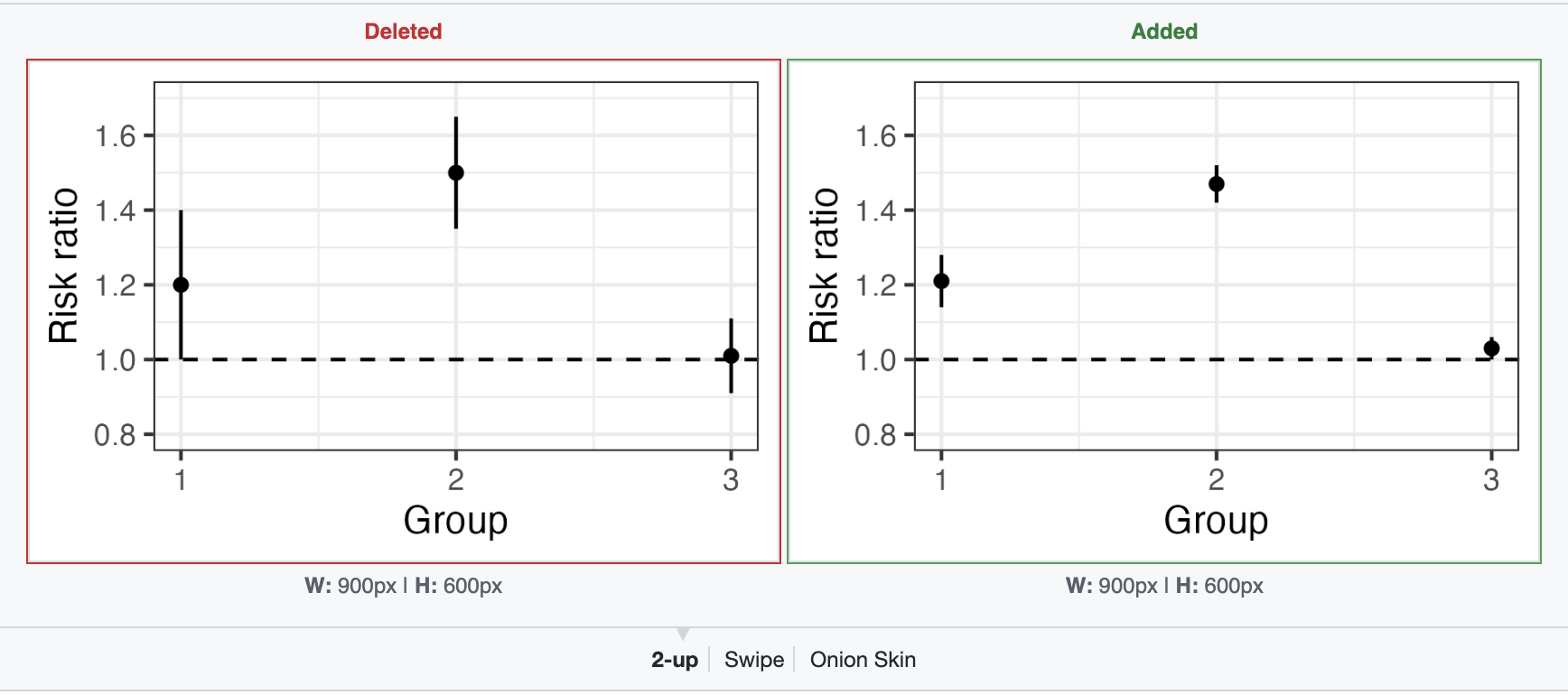

You can also track image files (e.g., png, jpeg), such as plots/other figures you create for a report. The benefit of tracking figures are the use of the image comparison tools in GitHub to see an image pre/post a change in the analysis. This can be super helpful when you have modified something in the analysis after having already written up some results. If you track the image, you can easily see how it changed (it being the point estimates and confidence intervals, of the slope of the regression line, or the shading of a colored map). This has the direct pay-off of making it much easier to revise the written result.

2-up comparison:

Swipe comparison:

Onion skin comparison:

❌ Dont’ track very large image files

One thing to be careful about is not uploading very large images like the ones that are generated by some GIS analyses (large maps). If you aren’t sure if you should track your image file, take a look at the file size. (I had a look at all of my repositories for epidemiologic analyses – most images were < 1000 kb. Some were between 1 MB and 4 MB – these were some maps and some images saved at higher resolutions.)

9.2.3 Documents

You can also track reports and manuscripts using GitHub. If these reports are written in a plain text language (e.g., R markdown, LaTeX) then they will render nicely on GitHub and, and permit you to see the “diffs” made to the document during a pull request. Tracking pdfs is permissible but you can’t easily see the “diffs” when they are updated. However, pdfs are easily viewable on GitHub. Tracking docx files is also permissible, but you can’t easily see the “diffs” and they are not easily viewable on GitHub (since they require MS Word to render them).

✅ Do track plain text reports like R markdown files

🤔 Consider tracking PDFs (easily viewable on GitHub)

❌ Don’t track Word documents (cannot view)

9.3 Things you definitely do not want to track

❌ Anything that is private or restricted or that you would never want to inadvertently share.

- This includes passwords, or API keys that you might use to extract data.

- For example, I have an API key to access Census data. I do not include this API key in my GitHub repository. There are methods for writing the code to still access the key on my personal computer without writing it out explicitly in the code.